Warning: Might contain some mild spoilers especially for those who have not seen series 5 (and 4) yet

Background:

Just as the 1960s are glamorised as the so-called “Swinging Sixties”, the 1920s has mostly been distorted through the lens of the so-called “Roaring Twenties” with its clichéd images of flappers, jazz, cocktails and the Bright Young Things. Those clichés are true to a certain extent but they were experienced by less than 1% of the entire population of the UK then and were mostly confined to Central London. For the majority, life more or less went on as it did before the war and any changes came slowly.

The reality of life during the 1920s was much more complex and interesting than the images of the flappers, fashion and parties suggest. This was the era when Hollywood became popular, consumer society expanded due to greater disposable income, women were taking their baby steps towards gender equality and full suffrage, and the Labour movement had taken the first step towards being a fully-fledged member of the Political Establishment; as well as advances in science and technology especially in the field of transportation and communication.

Of course, life wasn’t all good. Absolute poverty and disease was still rife, racism was very much endemic, there were threats to political stability and life choices were still more or less determined by birth, gender and class. However compared to even thirty years before, people had every reason to be optimistic during the 1920s; after all, the Great War had ended and a bright future was being promised not just by the state but also by demagogues and marketing men.

Some of our knowledge of life in the 1920s is gleaned through fiction and period drama with Downton Abbey being the latest to attempt to show the viewer what life like during the third decade of the 20th century. However, Julian Fellowes, instead of attempting to be original with his narrative has instead fallen back on the default clichés of the 1920s which are glaringly at odds with the reality for a great many people during this period. Chief among his major omissions are –

THE FINANCIAL POSITION OF THE ARISTOCRACY

How Downton Abbey portrayed this:

In Series 3, it was revealed that Lord Grantham unwisely invested the bulk of his wife’s dowry in a railway business that collapsed after the war. The family were then faced with the prospect of having to sell the Abbey and retrench. While some members of the family were resigned to the inevitable, Lady Mary wasn’t about to give up. First, she connived with her paternal grandmother to ask her maternal grandmother for help then when that failed, she nagged her fiancé Matthew to accept the money left to him by the father of his deceased fiancée. Matthew hesitated until he decided to finally do so, reaching an agreement with Lord Grantham and as a result his inheritance saved Downton again. He then embarked on a programme of economising and modernisation which was cut short due to his untimely death.

Come Series 4 and 5, all talk of economising seemingly has gone out of the window as the Crawleys are seen endlessly entertaining guests, hiring Dame Nellie Melba to perform (a move which has been criticised by music historians and opera experts), having a jazz band come for Lord Grantham’s birthday and hosting a lavish season for Lady Rose. Viewers are also surprised that the Crawleys have a Gutenberg bible, a Piero della Francesca painting and a London property (Grantham House).

The reality:

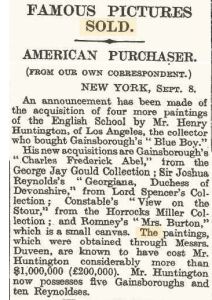

If the decline of the aristocracy began in the 1870s then the war and the 1920s speeded up the process further as increases in the rate of income tax and death duties further hammered the traditional landed aristocracy; this resulted into sales of works of art, jewels, silver and antiques. The auction of whole collections of art particularly Old Master paintings became front page news and as a matter of patriotic pride appeals were raised in order to save important works of art for the nation.

Meanwhile, acres of land were sold off for development into housing, factories and parks. London properties and stately homes were sold then demolished or converted to other use (such as schools, hospitals, offices, convents and monasteries), while others were handed to the National Trust or to the nation as places of historical interest to be opened to the public (Kenwood House being one example). Many people viewed the selling and demolition of Devonshire House (owned by one of the richest men in the UK at that time) in 1920 as symbolic of aristocratic impotence, not just on the political but also on the social and economic front as well.

This also meant that the aristocracy could no longer afford to live the same lifestyle they did before the war. House parties became shorter (and simpler affairs) or many abandoned them altogether due to several factors such as the loss of appetite for entertaining, less servants and most importantly, the expense both on the part of host and guest. Many accounts from this period survive about people dreading being invited to house parties given the lack of money (which was necessary for tips to be given to servants) and the expense of the clothes required for the still endless round of changes for the appropriate time of day and activity.

Hunting and shooting also were affected. Many aristocrats could no longer afford to become members or master of hunting packs owing to the expense involved while the carnage witnessed during the Great War meant that there was less inclination and interest in the wholesale slaughter of animals. The days when aristocratic men could bring down a large number of game birds in one afternoon were long gone.

In light of this, the Crawleys would hardly have been immune to the financial pressures of the 1920s especially as there are more than enough clues that they were solely reliant on agricultural land as their source of wealth and income. The Gutenberg bible, the Piero della Francesca painting and Grantham House would have been sold back in Series 3 (and technically the first two should have been sold the first time the Crawleys went bust in the 1880s as none of the surviving Gutenbergs and Piero della Francescas were in private hands by the turn of the last century) as well as acres of land and trinkets such as jewels, silver, other paintings. Given too the amount of money Lord Grantham lost in that ill-advised investment, any member of the family who bailed him out would have to have been in the same league as the Duke of Westminster and the Earl of Iveagh (the richest and second richest man in the UK respectively at that time) in terms of wealth.

What has been disconcerting is that the Crawleys’ attempts at tackling their financial issues are at best half-hearted, and miraculously they are rescued, either by a fortunate bequest or the sale of a valuable painting, so they do not have to retrench and sell in the ways that even the wealthiest peers had to do. Once Matthew is dead, all talks of economising are shelved then forgotten and come series 4 and 5 the family behave as if they’re billionaires awash with cash.

THE SERVANT PROBLEM

How Downton Abbey portrayed this:

Issues of logistics have always meant that the programme never has the full contingent of servants needed in a large house. Conspicuously missing are members of the kitchen staff required to do the baking and making of preserves and condiments, those whose main roles were to see to the candles and gas lamps and the outdoor staff (after watching the first series on DVD my father emailed to ask me why there was no gardener).

The death of William Mason and departures of Ethel Parks, then later Jane Moorsum in series 2 as well as the promotions of Daisy Mason, Thomas Barrow and Anna Bates in series 3 meant that certain positions were left vacant. This gave the opportunity to introduce three new servants as well as two who have made brief appearances in series 4 and 5, while a new lady’s maid (who has a mysterious past) for Lady Grantham was introduced halfway in series 4. A temporary footman was introduced in the last episode of series 5 and made another appearance in the recent Christmas special, whether he stays on remains to be seen.

The reality:

The Second Industrial Revolution (beginning around the 1870s) together with the expansion of the railways meant that there were greater employment opportunities for working class men and women. As a result, the first seeds of the “servant problem” were sown as many households struggled to attract people into service or stem the tide of the huge turnover of servants. Accounts from the late 19th century refer to the trouble with retaining good servants, many of who moved jobs, going on to other households for promotion or higher pay. There were also problems with trying to replace servants who had been sacked for being drunk, theft, falling pregnant or simply doing an AWOL from their jobs. In many communities, service was the only source of employment or the only option to escape the workhouse but for many others, especially after basic education became compulsory, there were other options available and more and more men and women preferred the factories and shops to being at the beck and call of the local lord, with hardly any time of their own for leisure.

The First World War further accelerated the servant problem as millions of men rushed to enlist and women took on the work men left behind. When the war finally ended, many were unwilling to return to a life of service while others who attempted to return found that their former employers could no longer afford to re-hire them. Those who managed to return to their pre-war posts were not replaced when they retired or passed away

While there were schemes to use service as a way to train orphans and women who had fallen on hard times as well as attempts to form a union for servants, these schemes were not very successful. As many households retrenched, the numbers of servants were reduced and many took on multiple positions. It was common to have households headed by a butler/valet and assisted by a housekeeper/cook. Other positions that gradually became merged included the head housemaid/lady’s maid or even housekeeper/lady’s maid. Junior housemaids and footmen were gradually replaced by day servants or agency staff for a particular event.

Downton Abbey has rarely explicitly addressed the “servant problem” and only when Molesley the former butler/valet of Matthew Crawley turned footman attempted to clarify his position once the other remaining footman had been sacked. The main issue with the way servants are portrayed in the programme has been addressed by critics and other bloggers; nevertheless, one problem I have is the circumstances by which servants are hired and retained. Would Lady Grantham have really hired Alfred Nugent simply because he was the nephew of her maid Sarah O’Brien? Or what about advertising for a lady’s maid In the Post Office window instead of through the proper channels, which led to the hiring of someone who had faked her credentials for some nefarious scheme to victimise a member of the family? What about Phyllis Baxter especially when her past was finally revealed? Another recurring complaint is about Thomas Barrow. He was about to be sacked due to bullying and theft (a very serious offence which spelt the end for a job in service). How he’s managed to stay on is a mystery and a constant source of bemusement and irritation for several viewers.

LADY MARY’S SUITORS AND WOULD SHE HAVE MARRIED AGAIN?

How Downton Abbey portrayed this:

The PR for Series 4 was mostly about how Lady Mary will pick up the pieces of her life after Matthew’s death; and apart from learning about estate management her story line in the next two series was about two men competing for her attention – a childhood acquaintance Lord Gillingham and Charles Blake, a civil servant who was later revealed to be in line for a baronetcy and an estate in Northern Ireland. While Lady Mary dithers over both men, in the end she chooses neither but a putative new suitor is waiting in the wings for series 6.

The reality:

The number of men who perished in the battlefields of the First World War has given rise to the pronouncements of a lost generation and the decimation of the “flower of England’s youth” which sounds hyperbolic to modern day ears but there is a kernel of truth in it. There is enough evidence and recollection from those who were children during the interwar period that while there were children and middle aged to old men there were hardly any men in their mid-twenties to thirties to be seen in the streets.

There were those who managed to return home alive but were physically disabled owing to war wounds for instance amputated arms and limbs, facial disfigurement or respiratory issues due to inhaling poison gas. Others who returned might not have been missing an arm or a leg or disfigured but were wounded in mind with many suffering from shell shock or others turning to the bottle. Still others who felt guilty for having survived while many of their comrades died or were severely wounded became reclusive and succumbed to depression.

While the marriage rate did go up during the interwar years those women who were in their late twenties to their early thirties when the war ended were more or less resigned to a life of widowhood or spinsterhood. Many took advantage of this lack of prospects for marriage and motherhood as an opportunity to forge an independent life as career women and entrepreneurs.

One of the issues I have with Downton Abbey since series 2 is how the First World War has been swept under the carpet when in reality its immediate effects continued to be felt until the eve of the Second World War. This is shown most obviously with the story line of Lady Mary and her suitors; and leaving aside that it is quite difficult to tell both Lord Gillingham and Mr Blake apart (and the putative new suitor is hardly an improvement), she would have been in her thirties by the 1920s and by the standards of the time, middle aged. Eligible men would have more likely preferred younger women without a child; and with the crop of new debutantes emerging every year then Lady Mary would have faced stiff competition indeed. It’s hardly likely that with a surplus of women of marriageable age two men apparently sound in mind and limb would be happy to remain single for five years on the off chance that a woman might make up her mind to marry one of them; especially as neither of them seem to be that much in love with her. It’s much more likely that surrounded by hordes of women husband hunting one or both would have been snapped up almost before they were out of uniform.

Another thing that baffled several viewers is the absence of any disabled veterans walking the streets and among Lady Mary’s line up of suitors; which again is consistent with the programme’s collective amnesia over the war and its aftermath. Looking at demographic patterns after the war, it is highly unlikely that Lady Mary would have married again and if she did, her second husband would have either been significantly older than she was or someone her age but very likely wounded in body or mind.

CONCLUSION:

In my first blog entry, I have mentioned the main gripe that many critics and bloggers have about Downton Abbey but as a history anorak, the main problem I have with the programme since series 3 is that there no context in its wider world, no sense of what other peers are having to do or what’s going on outside the gates. True there were no major historical events on the scale of the First World War during this period but the 1920s themselves were a period of major change for everyone in society, high and low. Not all of them were glamorous and exciting but they helped shape society and institutions as we know today.

The period between the wars is one that is slowly passing out of living history as more people who grew up during that period are dying off. The time will come when there will be no-one alive who remembers the 1920s and it’s a shame that Downton Abbey has squandered the opportunity to be more imaginative with its story lines and hold up a mirror to an era of change beyond the well-worn clichés of flappers, jazz, cocktails and parties.

Further reading:

Martin Pugh. We Danced All Night: A Social History of Britain Between the Wars (London, 2009)

Jeremy Musson. Up and Down Stairs (London, 2010)

Lucy Lethbridge. Servants (London, 2013)

Pamela Horn. Country House Society (London, 2013)

Pamela Horn. Life Below Stairs: The Real Lives of Servants, the Edwardian Era to 1939 (London, 2012)

Pamela Horn. Flappers: The Real Lives of British Women in the Era of The Great Gatsby (London, 2012)

Mollie Moran. Aprons and Silver Spoons (London, 2013)

Andrew Marr. The Making of Modern Britain (London, 2009)

David Cannadine. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London, 1990)

David Cannadine. Aspects of the Aristocracy (London, 1994)

Juliet Nicolson. The Great Silence: 1918-1920 Living in the Shadow of the Great War (London, 2010)

Virginia Nicholson. Singled Out (London, 2008)

Sian Evans. Life below Stairs (London, 2011)

Mark Girouard. Life in the English Country House (Yale, 1978)

David Reynolds. The Great Shadow: The Great War and the Twentieth Century (London, 2014)

Jeremy Paxman. Great Britain’s Great War (London, 2014)

http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/real-downton-abbey-decline-country-house-lifestyle/

Amen, amen, and amen. 🙂 Time to go read some excellent fanfiction instead! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks and am in two minds about fan fiction while some are well written others aren’t as good and anachronistic as well.

LikeLike

I am late to this, but always interested in your view of this popular series. I have watched all of them, as I was previously a fan of (the far superior) ‘Upstairs Downstairs’, and I have long been fascinated by the period between the two world wars.

It is as you say, merely a soap opera, and just on a grander scale than ‘Eastenders’, or any other popular series in the same vein. Reading about it in magazines, and on the Internet, I came to the conclusion that success in America was its undoing. ‘Dallas’ in Yorkshire; intellectual content reduced for international consumption, and well-dressed set pieces for the delight of those who have no knowledge of the period.

It has to still be worth it though, as long as Maggie Smith remains, to deliver those lines.

If I want to see what it might have been like, I will watch ‘Remains Of The Day’ again, or ‘The Shooting Party.’

I look forward to your appraisal of the ‘final’ series.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for your reply and I agree with you that Downton’s success in America and subsequently overseas proved to be its undoing. Foreigners would barely have a clue about our history and its nuances and in effect by focusing on set pieces, romances, clothes, scenery and the crude pastiche of aristocratic lifestyle was pandering to the lowest common denominator.

Maggie Smith and Penelope Wilton are generally the only reason I think why people carry on watching. Not to mention as well seeing as how bad this has become, how worse it can get.

Watch this space for an appraisal of series 6 and do check out for our take on some aspects of the previous series.

LikeLike

I’ve found this column very late but am thoroughly enjoying it! Of course your comments re the complete lack of young men in England following WWI is absolutely right . It’s ludicrous to think that a widow w/child (read:heir)& completely tied-up finances would have been pursued. Certainly not instead of that debutante heiress who Gillingham abandoned!

Your earlier pieces re Mary’s ‘seasons’ are totally on the mark. There’s no way that any daughter of an Earl who’s estate was entailed away would have been allowed to be single at the end of her first season. All of the daughters of such a wealthy family , including Edith & Sibyl, would have had good portions (dowries) & the family would cut a deal to ensure they were settled ASAP.

My own family background is European-Jewish upper Middle class, my grandparents house in pre-WWII Vienna was very similar to Isobel Crawley’s, including the type of servants (no modern appliances & cheap labor = plenty of domestic help also for middle classes).

Marrying off daughters w/dowries was a major occupation. Money went to other money or to status, poor sons from good families frequently married daughters of families with good businesses but no sons.

Even for middle class Jews a chauffeur was an unacceptable spouse!! If a daughter ran away with a servant (there were also Jewish servants) there’s no way she would have been let back in – never mind the husband!!

I’m looking forward to reading all of your columns from the beginning.

All the best

Deborah

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Deborah,

Many thanks for your comment and your insights. I’ve also enjoyed reading about your family history and the way you described the world your grandparents grew up in and the attitudes prevalent then which you’ve hit the nail on the head. Making a good marriage was very important, sure marrying someone of equal wealth and status was important but if one was lacking then the other could compensate for it hence the exchange principle – money for status and vice versa.

I hope you enjoy reading the rest of the blog and I look forward to hearing more from you.

LikeLike

Wait! The Crawleys own a Gutenberg Bible? WTF! I suppose it’s not quite as bad as the main witch in the Salem series have Primavera over her fireplace, but that’s still pretty absurd.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reportedly they do which I find hard to believe but a friend of mine has speculated that it could be a fake. And especially as by the late 19th century none of the bibles were in private hands then its more likely what they have is a fake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would have been a WAY more interesting scenario to write. It would have given a window in the way the 18th and 19th century aristocracy occasionally did such things, and it would have created drama. “It’s a fake! We can’t possibly sell it for real money!” “We can either sell it and hope they don’t realize it’s a fake, or lose Downton!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even if it was fake, it would have still sold fairly well for historical reasons in order to show how much Gutenberg really transformed printing in Europe. Not to mention yes, to show how the Crawleys have always been gullible – not only have they been manipulated by their own servants but even by outsiders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And let’s be honest, Lord Crawley doesn’t have a lick of business sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

None of them do really. I’m from the UK and when Downton first aired, the first thing some critics noticed is how thick and stupid Cora was and that never changed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a certain irony of Fellowes trying to glorify the aristocracy and instead demonstrating how useless they are in the 20th century.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And that was the reality which I’ve pointed out in my latest blog. By the 1920s, the aristocracy was pretty much a spent force.

LikeLiked by 1 person