For part 1 – see here

Delayed Reaction – food rationing

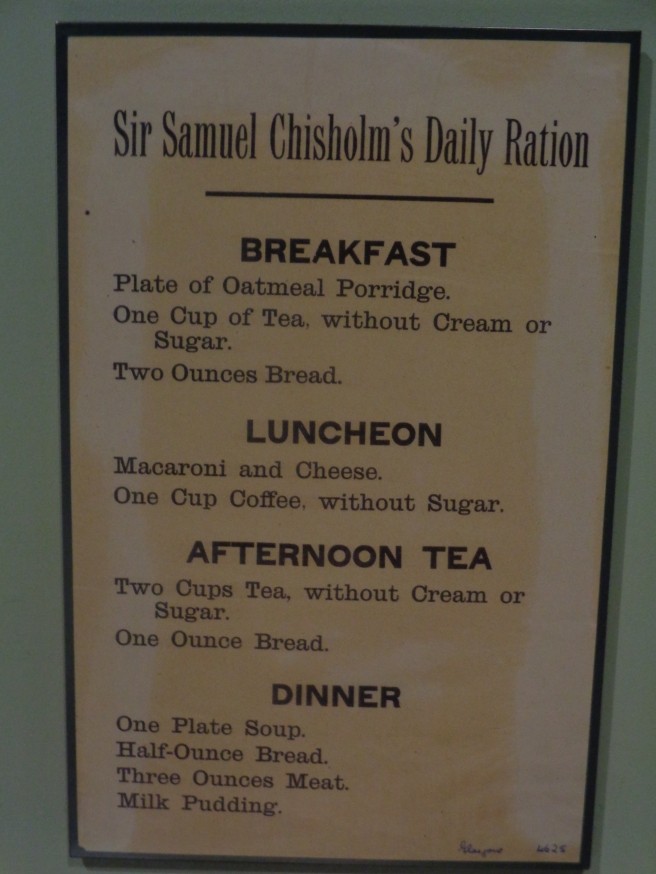

Another example of this delayed reaction I mentioned before is with regards to shortages and rationing. As early as late 1914, the difficulty in obtaining goods from other countries resulted into price hikes for both essential and non-essential goods. By around 1916 there were already fabric shortages that helped accelerate further the demise of Victorian mourning customs. There was also less coal to go around so several households resorted to burning “waste paper bricks” or installing “coal saving” chimney pots. Crucially however was in 1917 when the Germans decided to engage in unrestricted U boat warfare to starve Britain into submission. In April 1917 alone Britain lost 800,000 tonnes of shipping – Germany knew that the UK depended a lot on imported food from abroad and decided to strike where it would hurt Britain the most – as Georgina Lee noted on 29 January:

The submarine menace is now acute. These islands are faced with a real shortage of food….[t]he daily toll of ships is growing heavier, and the Germans are seizing upon the U-boat as their last chance.

The submarine menace is now what we fear most. It really marks the death grapple between Britain and Germany.

By the end of April, Lillie Scales noted in her diary that “last Wednesday 40 ships over 1,600 tons were reported as having been torpedoed or mined,” Lord Devonport, the food minister initially called for voluntary rationing and Britain was forced to have two meatless days a week, while from October 1917 bakers were allowed to add potato flour to bread. Georgina Lee on 2 February 1917 recalls the amount of food consumed by her household:

We do not exceed this liberal allowance already, at least we have not lately. As we are seven in the house, I reckon we can have weekly:

13 loaves of 2lbs each, with

1½ lb Flour for puddings etc.

1/2 lb Flour for Cake

As for sugar, for weeks past I have imposed a limit of 5lbs for the household. Now I see I can use another 1/4lb, if I can get it! It has been very difficult to procure sugar at all, most grocers absolutely refusing to supply any. But my dear Army and Navy stores allow a certain fixed proportion on grocery orders.

The meat will be more difficult as the 2 ½ lbs include bone. It includes bacon for breakfast and ham so it will mean a great deal of goodwill and patriotic loyalty on the part of women, because these rations are at present left to our honour to enforce. There is to be no system of tickets yet, as in Germany. But the Government will resort to compulsion if the country does not respond.

The inefficiency of British agriculture and the commitment to free trade was one of the factors why Britain imported the bulk of its food from abroad. There were other factors as well as Jeremy Paxman noted, the British, he wrote, “lived by trade, and the growth of imperial power had rendered the country unable to feed itself any longer.” This overdependence on imported food meant that supplies were vulnerable to enemy attack and since the war broke out, people had generally made do with substitutes for staples such as butter, while newspapers and magazines published recipes especially for cakes that required no butter, milk or eggs. But this wasn’t enough and by 1917-18, shortages were becoming more acute and endless queues for even the most basic of food stuffs were becoming common. The government’s initial response was to promote voluntary schemes such as “Eat Less Bread” through the office of the Food Controller led by Lord Devonport with the support and encouragement of the royal family. But these were not really successful and as more ships were sunk, shortages became even became more acute and the cost of food went up even further; the state was forced to come up with compulsory rationing especially on food stuffs such as butter, sugar, flour and later meat. The rationale behind rationing was to ensure that everyone received their fair share and would result into fewer queues in shops and discourage general panic that could damage morale. To help enforce rationing, the government made food hoarding a crime and several prominent and wealthy people fell foul of the law such as the writer Marie Corelli who was fined £50 for hoarding sugar despite her protestations that the sugar was for jam she intended to give away. A massive fine of nearly £700 was imposed on a Newcastle shipping magnate Rowland Hodge after he and his wife were caught hoarding over a ton of food including sugar and flour.

Apart from making food hoarding a crime, the government also extended the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) to cover food production. Other legislation were introduced such as the banning of throwing rice at newlyweds, fines for wasting food (by 1918, nearly 30,000 people were fined for such an offence), regulating what farmers could feed their livestock and setting minimum prices to discourage war profiteering as well as making the latter punishable by fines or imprisonment. But there was more to rationing than coercion and employing the stick, for instance the Game Laws were relaxed to ease food shortages, as Georgina Lee recalled in her diary:

13 February

The Game Laws of England! They too have had to make way for the necessities of England at war. Not only is it illegal to feed game birds on corn or maize, but game is no longer protected. Anybody can shoot pheasants and any other game on the land on which he is tenant. This is partly to use all available food, and also to prevent these birds eating the precious crops. Some few weeks ago it was the shooting of all hunting packs, to save their food; and naturally too of foxes to prevent them eating poultry.

There were also campaigns to encourage people to plant vegetables no matter how small the patch of land was (and yet again, the royal family did set an example by using the gardens at Buckingham Palace and other royal residences to plant potatoes and the like) as well as exhortations to eat bread substitutes such as rice and maize and using less refined flour or potatoes to bulk out homemade bread. Magazines, newspapers and cookbooks were on hand to offer advice on how to eat well despite rationing – a noted example was May Byron, a writer known for her popular biographies and cook books. As she exhorts in her war time cookery book, May Byron’s Rations Book, “[i]f you cannot have the best, make the best of what you have” and her recipes were filled with tips on how to stretch out meagre rations and using substitutes for ingredients that were expensive or hard to obtain.

The fact that Britain was importing most of its food from abroad and that the war had meant both rising costs and later food shortages makes a nonsense of Jessica Fellowes’ claim that “food was relatively plentiful” and that “rationing didn’t come in until near the end of the war,” (but perhaps she didn’t notice that those two statements contradict each other). Certainly voluntary rationing was encouraged and official rationing and the issue of ration books did not start until the beginning of 1918 with the issue of ration books with coupons for sugar, butter or margarine and meat. Throughout 1917 and 1918 regulations and penalties against waste, hoarding and profiteering became increasingly stringent, which does not suggest that food was “relatively plentiful”. It’s true that the Crawleys would have been cushioned by the fact that there was a home farm that supplied nearly all the family’s food but they would have still been subjected to government legislation concerning what to feed and not to feed their livestock, there would have been fewer men working on the farm and given that the Crawleys seemed to have resisted mechanising and implementing more efficient means of farming then there would have been less food to go around. Crucially there would be difficulties with imported essentials such as flour and sugar as well as coal. We do not see the Crawleys really coping with shortages in the same way as majority of their real life counterparts did, and yet again we don’t see them taking the lead and initiative when it comes to offsetting and easing shortages in food. Also, if the Crawleys haven’t mechanized (and a comment in series 1 suggests that haven’t), they are reliant on horses, and many of these horses would have gone, having been requisitioned by the army. The ones that are left are the old ones and they work less hard and need more care and feeding, hence less food is produced.

Even before compulsory rationing had been introduced, many real life aristocrats had been finding ways to cope with shortages. As Pamela Horn writes, as early as 1915, the duke of Marlborough had already introduced sheep into the formal gardens at Blenheim to replace the gardeners who had enlisted, and turned over the gardens for the planting of vegetables. Mabell Countess of Airlie, apart from her duties as a lady in waiting to Queen Mary and war work involving nursing training, was also holding the fort at the Cortachy estate as her sons and many of the estate workers had gone off to fight. She was heavily involved in ensuring that the estate was doing its part in the nationwide drive to be more self-sufficient in terms of food. In her autobiography Thatched with Gold, she recalled: “My entire horizon was bounded by potatoes. Every vine house was stuffed full of them; even the little hut at the back of the gardens was stacked with potato boxes from the floor to the roof.”

As mentioned in part 1, the Crawleys being the leading local family would be expected to be following the rules and seen to be following the rules, and that would include food rationing as well. Even before the diktat from the government arrived, Robert and Cora should have been leading by example and instructing Mrs Patmore and the rest of the kitchen staff to ensure that nothing was wasted: and even before the food shortages became noticeable and unavoidable, rising costs on goods and services as well as increase in taxation would mean that the Crawleys would have to resort to belt tightening measures long before 1917. It’s all well and good for Carson to pontificate that “keeping up standards is the only way to show the Germans they will not beat us in the end” but as the war dragged on, the casualties mounted and food became increasingly scarce Carson’s concern about proper place settings and objecting to maids serving at the table are not so much amusing as irrelevant and petulant. However, the rationing only becomes a plot bunny for when Matthew is set to marry Lavinia Swire and Mrs Patmore has to make the cake for the festivities. Rationing then becomes a crude bolt on plot device and trivialises the fact that Britain could have lost the war and that revolution could have been possible if it wasn’t for rationing both voluntary and through legislation, the convoy system and the realisation that to survive, people would have to rely more on home grown food and be canny and flexible. As May Byron confidently asserted:

Now, when faced with a crude incontrovertible fact that we live in an island, and that nearly all our food has been coming for outside that island, there is no doubt that the present rude awakening should be – in the long run – be very much to our advantage. ‘It’s an ill wind that blows nobody good.’ To begin with, a fools’ paradise is a weakening and demoralising habitation; to go on with, we are now compelled, willy-nilly to learn the use and value if expedients, of substitutes, of skilful cookery….I conjecture that, sooner or later, we shall emerge from this dire emergency a great deal cleverer than we were before; having acquired all sorts of knowledge, and exploited all manner of possibilities, which we should have regarded with a stare of blank bewilderment in 1913.

The servant problem – grabbing opportunities with both hands

When the First World War broke out, men of all classes rushed to enlist and this meant particularly for the aristocracy that their male servants both outdoor and indoor as well as estate farmers and tenants went off to fight; leaving them with those who were too old or too young to enlist (although this didn’t stop those who were too young from lying about their age). Outdoor members of staff such as carpenters, gardeners, gamekeepers, chauffeurs, coachmen and grooms particularly were valued by the armed services as they had skills that were useful and needed in a time of war. Country house servants were also generally seen as fitter and healthier than their counterparts in the city and were attractive recruits. There was also the appeal to patriotism – as Country Life asked its readers not long after the outbreak of war:

Have you a Butler, Groom, Chauffeur, Gardener or Gamekeeper serving you who, at this moment should be serving your King and Country? Will you sacrifice your personal convenience for your Country’s need? Ask your men to enlist TO-DAY.

The aristocracy also heavily encouraged their servants and estate workers to sign up; offering incentives such as keeping their jobs open for their return when the war ended (and the expectation was it would be over before Christmas), extended pay and continuing to pay their salaries to their dependents. More encouragement came from the state through the establishment of Pals’ Battalions and propaganda posters depicting German bombings of British towns and cities. Finally in 1916, the government introduced conscription which meant that men who fitted the criteria determined by the government had to fight. Conscription meant that more able bodied men went away to fight and with a few exceptions many aristocratic households found their homes almost exclusively staffed by women.

The war however also took away many of the female servants. Better pay and shorter working hours led many maids to leave service and take on work in munitions factories. Although the work could be difficult, dirty and dangerous the benefits included weekends off and nutritious and filling meals served on site. For the first time, many of these women had more money, more free time and were not in the beck and call of someone nearly 24 hours a day and seven days a week. The munitionettes eagerly partook in the nascent consumer culture of the period as they went to the pictures, tea rooms and restaurants as well as purchasing cosmetics, scent, clothes and accessories. Manufacturers and service providers realised that there was a new market to be tapped and the munitionettes would help pave the way for the growth of a consumer culture among the working class following the war.

Although the servant problem began during the late 19th century, the war further accelerated this issue. As the men went away to fight and the women moved on to more profitable war work, the country house many of which were located in the middle of nowhere suddenly was seen as limiting and it was preferable to be at the trenches or in a noisy factory. Rising costs and higher taxes meant that it was unaffordable for the aristocracy and upper middle class to keep the same number of servants before the war and resulted in many of them being unable to keep their promise of holding jobs open for those who had gone off to fight.

In light of this, it’s baffling that apart from Thomas and later William, none of the downstairs staff at Downton Abbey has expressed any interest in leaving the confines of the Abbey to either serve at the front or head off for more lucrative work. More so especially the women as Fellowes and the PR (especially during the last three series) have been yammering about “strong women” who are “substantial individuals” and are not “wilting damsels:” except we don’t see that either with the upstairs or downstairs female characters. Someone like Anna or Daisy would have been prime candidates to leave the Abbey to find better opportunities elsewhere but instead we get Anna snivelling and pining for Mr Bates as part of what would become a long running misery saga, and Daisy does nothing but whine and sulk despite the efforts of good Samaritans such as William and Jane.

There’s Ethel the second housemaid who constantly goes on about “wanting the best” but yet continues to stay in service when she could go to a munitions factory and get paid more and work shorter hours and days. Of course there is the irony that her story line which involves her getting pregnant out of wedlock by one of the officers who is a patient at the hospital and getting sacked as a result is accurate and could have happened: especially as pregnancy out of wedlock was frowned upon by all social classes and a working class woman like Ethel would have much to lose.

Another irony is that the most accurate story lines in this series featured those downstairs. Apart from Ethel, there’s William being conscripted and his belief that they are fighting a just war, Lang the valet who was invalided out of the army and suffers from shellshock, and war widow Jane who replaces Ethel and finds a kindred spirit in Robert. However it’s a shame that many of these story lines were not explored more thoroughly and this was not helped by the ropey timeline and the speed with which Fellowes explores the First World War.

Conclusion and aftermath:

In his notes on the script for the 2011 Christmas special, Fellowes claimed that he set the special at the end of 1919 with the traditional servants’ ball held after New Year in 1920 in order to “allow the audience to grasp that the next series would take them into yet another era, leaving the war far behind.” And that in my view was a foreshadowing of the problems that would plague the programme in the last four series, especially the last three after Dan Stevens decided not to renew.

From series 3 onwards, there was a collective amnesia about the war in Downton Abbey. As one critic has pointed out, Downton simply retreated to the past when money was still plentiful and they could party like it was 1912 all over again. We do not see any war veterans begging in the streets, there’s nothing about unemployment going up as soon as the demobilised men return from the front, no mention of maimed veterans or further rises in taxation or sales of land and property and as many viewers cheekily pointed out, no disabled war vets among Mary’s suitors: and none of the paranoia about revolution, Bolshevism and socialism. Watching Downton you could be forgiven for not knowing that by 1918 three major ruling dynasties – Habsburg, Hohenzollen and Romanov – had been overthrown, in the case of the latter, bloodily and violently, nor the widespread fear that revolution and radical social change was likely to happen in Britain. Unlike real post-war Britain, the war becomes forgotten until it’s used as a plot bunny in series 5 to give redundant characters something to do and even then it was a delayed reaction – why does it take until 1924-25 for the village to have its war memorial when similar edifices were already springing up across the country as early as 1919 and the Cenotaph in London was built and dedicated in 1920 following the burial of the Unknown Soldier at Westminster Abbey?

Although with hindsight series 2 is seen as one of the more decent series (the other being series 1), this marks the start of the often baffling swerves in characterization for the sake of the plot, Robert in particular. A man like him who was in the regular army would have been recalled to the colours as soon as possible or if sending him to the front was not possible, then he would be placed in charge of a training depot responsible for training some of the volunteers who have signed up. One can see how Fellowes writes to the plot and not the character from that and what happens in series 3 when apparently Robert – a Lord Lieutenant and representative of the Crown – can barge into the Home Office and DEMAND that the Home Secretary perverts the course of justice for a Fenian rebel – which is something that I think a lot of people didn’t realize he was doing. Not to mention as well indulging in breaking in and forgery in order to stop a putative royal scandal in the 2013 Christmas special, a plotline so thin and so ridiculous that people laughed at it for its lack of credibility and sheer ludicrousness. If he can do all of that, then he can confront the War Office and demand a posting. But that wasn’t the plot so it didn’t happen although it was likely that Fellowes didn’t even think of him doing that.

A family like the Crawleys would have been expected to step up to the plate and do their bit. They would have taken the initiative and not wait until 1917 to be dragged kicking and screaming to open their house as a hospital when in reality a lot of homes were already ready to receive casualties not long after the outbreak of war. In the end, the war was simply treated as if it was a little local difficulty in the way of Matthew and Mary getting married – it barely inconveniences the family for all their foot-stamping over the hospital – and for all the yammering about “Downton at war” and claims that the programme is chronicling a time of rapid change, we barely see any of it. All the changes are simply cosmetic, there are no attempts to really explore what the war meant for everyone and how they were affected. The servants and family assemble to mark the armistice on 11 November 1918, Robert makes a poignant comment about how many men have been killed on the estate and that’s all, folks. Global war and slaughter on an industrial scale done, dusted and dealt with. Once the war is over Downton Abbey reverts to the old ways as if nothing had happened, and as many viewers pointed out, the 1910s where so much happens is covered in 2 series while the 1920s where nothing major really happens is dragged out for four. So much dramatic and narrative potential, and all wasted.

It seems that nothing must stand in the way of derailing the destiny that has been set for Matthew and Mary – to the point of staging a mis-diagnosis and miraculous recovery for Matthew so he can marry his true love and sire the next generation – as well as what Professor Katherine Byrne calls the programme’s “socially conservative” message. I will even go one step further to say that the war must not stand in the way of the fairy tale that has been constructed around Downton as demonstrated by the collective amnesia about the war afterwards except in series 5 as a plot point, when in reality it was still present in people’s minds right up to 1939 and of course beyond to the present day.

Further Reading:

Gavin Roynon (ed) Home Fires Burning: The Great War Diaries of Georgina Lee (Stroud, 2006)

Jerry White. Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War (London, 2014)

Terry Charman. The First World War on the Home Front (London, 2014)

Kate Adie. Fighting on the Home Front (London, 2013)

Lucy Lethbridge. Servants (London, 2013)

Fiona (Herbert) Countess of Carnarvon. Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey: The Lost Legacy of Highclere Castle (London, 2011)

Julian Fellowes. Downton Abbey: The Complete Scripts Series 2 (London, 2013)

Jeremy Paxman. Great Britain’s Great War (London, 2014)

May Byron (with introduction by Eleri Pipien). The Great War Cookbook (Stroud, 2014)

Lillie Scales. A Home Front Diary, 1914-1918 (Stroud, 2014)

Brian and Brenda Williams. The Pitkin Guide to the Country House at War 1914-1918 (Stroud, 2014)

Jessica Fellowes. The World of Downton Abbey (London, 2011)

Simon Greaves. The Country House at War (London, 2014)

Jane Dismore. Duchesses: Living in 21st Century Britain (London, 2014)

Diana Cooper. The Rainbow Comes and Goes (London, 1958)

Ian Kershaw. To Hell and Back: Europe 1914-1949 (London, 2015)

David Cannadine. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London, 1990)

Andrew Marr. The Making of Modern Britain (London, 2009)

Anne de Courcy. Society’s Queen: The Life of Edith Marchioness of Londonderry (London, 1989)

Mabell (Ogilvy) Countess of Airlie and Jennifer Ellis (ed.). Thatched with Gold: The Memoirs of Mabell Countess of Airlie (London, 1962)

Pamela Horn. Country House Society (London, 2013)

Katherine Byrne. ‘Adapting Heritage: Class and conservatism in Downton Abbey‘. Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice Vol 18 no 3 (Aug 2013) pp. 311-327.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01xtx6f/p01xtwvm

Britain on the Brink of Starvation: Unrestricted Submarine Warfare