Downton Abbey’s first series in 2010 which opened in 1912 with the sinking of the Titanic ended in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War- and such was the popularity of the first series that a second one was commissioned by ITV and was telecast in 2011. The second series with the First World War as the backdrop was set between 1916 and 1919, depicting the lives of the Crawley family and their servants during the war as the likes of Matthew, Thomas and William go off to fight and the Abbey itself is turned into a convalescent home for officers.

Although the quality of Downton’s narrative began to suffer from series three onwards, the plot holes were already apparent even with the first series and series two was no exception. Since the First World War was supposedly the main focal point of the second series, surprisingly there was little to no exploration of the conflict and how this war was unlike what had gone before, let alone its effects on millions of people at the time or for years to come. In retrospect its only reasons for inclusion in series two seem to have been a) it’s 1914 – Fellowes can’t actually ignore that it happened and b) to throw obstacles in the way of the romance of a dull couple. Chief among the major omissions include:

Lopping off two years from the war:

Series 2 of Downton Abbey opens with the Battle of the Somme and in the published scripts for the second series, Julian Fellowes explains why he decided to jump ahead to 1916 rather than continue with 1914 and have the family doing in 1916 what they should have been doing in 1914:

The challenge naturally, was how to cover the war. In the end, we decided that, just as we had opened Season One with the news of the Titanic in order to pinpoint where we were, similarly we would open Season Two on the battlefield, so there would be no mincing about. From the first scene the audience would know the war has begun. The other decision we made was that we would go forward two years into the middle of the fighting. This was partly because, after the declaration of war, as with all wars, there was a kind of slow-burn start-up, when we wanted to begin with a big bang, literally, but it would also mean that all the characters could have war back stories as the series opened…….[t]hey could jump out of the screen, like Athena leaping from the head of Zeus, fully formed fighters, caught in the Sturm und Drang of the Battle of the Somme.

I find this reasoning problematic and contradictory, never mind the offensiveness of seeing two years of all-out war and death described as ‘mincing about.’ The First World War was the first total and mechanised war in history and as soon as Britain had declared war on Germany, the whole war machine swung into action – land and sea transport were requisitioned to transport troops to the front and to provide emergency medical care, mobilisation was ordered, men who had been in the army were recalled to the colours and unused and idle land seized to set up military training camps and for food production. The civilian population both in the city and country was caught up with the country gearing up for war as the railways began to transport men and supplies to the front, men rushed to enlist and horses were requisitioned to be used for transport and by the cavalry.

In addition there was the also the fear of invasion. In the years before the outbreak of war and despite the confidence that the might of the Royal Navy would protect Britain from foreign invasion, the arms race against Germany and the prevalence of scare stories in the press and novels featuring spies and a possible invasion by the likes of Erskine Childers, John Buchan, Arthur Conan Doyle and Joseph Conrad stoked fears of Britain being invaded. When war finally broke out, the government was so concerned with the possibility of invasion that Boy Scouts and local men – mostly those who were not eligible to fight – were engaged as look outs along coastal areas.

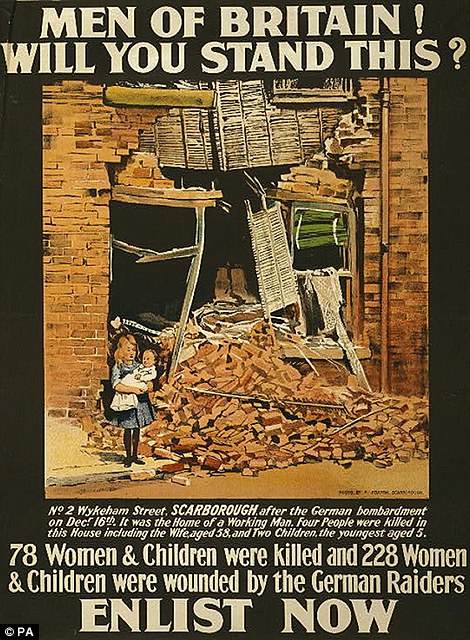

This fear became even more apparent when Whitby and Scarborough were shelled by German warships in November and December 1914. Not only was this the first time the civilian population had been targeted, they had no way of knowing it wasn’t the prelude to invasion. Jessica Fellowes claimed in The World of Downton Abbey that because Downton Abbey was “situated in the north of England in the middle of the countryside, it would not have suffered the frightening spectre of fighter planes overhead or the distant echo of bombshell.” But this is not exactly true as given where Downton Abbey is located, the village would have been near to both towns and not only would have the Crawleys, their servants and the rest of the village have heard of the bombardment but there would be general fear among the populace. And this fear spread to other parts of the country as well as Georgina Lee wrote in her diary:

December 16

The first German shells have fallen on England. This morning at 8am some German cruisers were sighted off Whitby, Scarborough and Hartlepool. A few minutes later they started shelling the three towns causing many casualties and damage to buildings and property. Everybody seems to think it a pity for those who have to suffer, but a very good thing for the country generally, which will at last be roused to the seriousness of the situation. The cruisers bombarded for half an hour, the, on sighting British patrol vessels, they disappeared in the mist.

December 17

The shelling of the three towns is more serious than was reported yesterday. Altogether 40 people have been killed and several hundred wounded, all civilians, including children and babies. Whitby Abbey, a priceless old monument, was much damaged.

It is mortifying that the German cruisers were able to come 400 miles, to bombard three cities and return to Kiel, without any of our fleet being there to stop them. How did they get through? On their way back they sowed mines in the North Sea which have already sunk three of our merchant steamers.

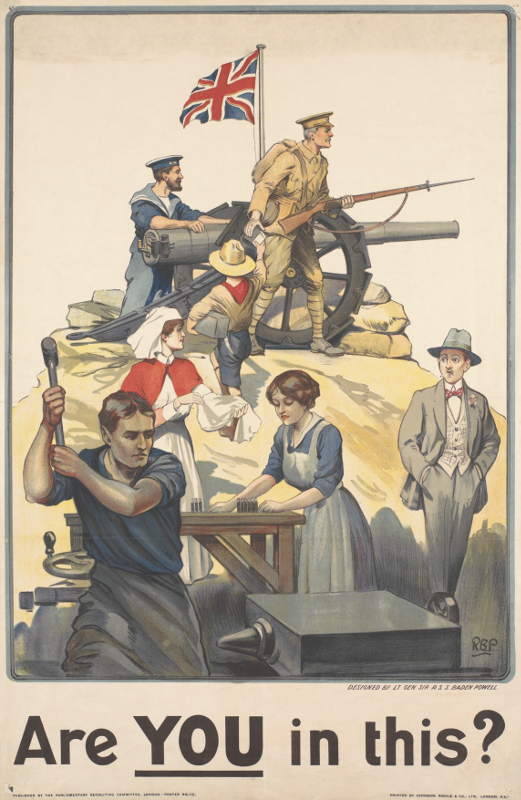

And while it’s true that the Battle of the Somme was “a great bloodletting, and a massive hideous event because so many men died” the early battles were no picnics in the park either: when Antwerp fell to the Germans in late 1914, that heightened fears of a German advance into France and finally crossing the Channel to invade Britain. There was also the retreat from Mons and the Battle of Loos in 1915 where despite great advantages from the Allied side, the British and the French failed to break through the Germans lines and the British suffered appallingly high casualty rates. All these would have been major headline news and all the more because even during the first two years of the war, there were already large numbers of men who have gone off to fight and millions more rushed to enlist after Lord Kitchener’s appeal for more men and encouraged by reports and propaganda posters depicting German atrocities in Belgium and the shelling of Whitby and Scadrborough.

Fellowes’ comments above I believe reduces the death and slaughter from 1914 to 1916 as nothing more than something he’s decided are not sufficiently dramatic for his purposes. The fact that so many civilians especially women and children died during the raids on Whitby and Scarborough sparked outrage, drove more men to enlist and in the case of Downton Abbey provided a good avenue for the characters to articulate what would have been the reactions of ordinary people as the bombardment brought the reality of war in a way that was not possible in earlier conflicts.

Delayed Reaction – reluctantly falling in to do their bit:

In earlier blogs discussing the problems with Downton Abbey’s plotting and story lines, one of the issues that always recur is what I call “delayed reaction” which is something that is seen especially in the last three series. This “delayed reaction” began with series two – not content with lopping off two years from the war, Fellowes also decides to delay the role that the Crawleys will play during the war as he writes in his notes to the published scripts:

First of all, to take the house and its residents into the conflict, we start with a commitment to the soldiers at the front, and a fundraising event, but we do not yet suggest they should make any great sacrifices. This is, if you like, the transitional stage, when the family and staff realise that they’ve got to get behind the war effort and do their stuff but they haven’t really accepted the degree to which they can be helpful, because it will disturb their daily lives profoundly. I think it’s realistic. They’re well intentioned, patriotic, loyal, but not yet quite ready to sacrifice their way of life.

A cursory reading of the present Countess of Carnarvon’s biography of her predecessor Almina the 5th countess tells us a different story. Already known for her work with the sick on the Highclere estate, as well as nursing her own husband who had been left weakened by a motor accident in the early 1900s, the 5th countess had decided to turn Highclere Castle into a hospital in the event of war breaking out. She also began to undertake a more formalised nursing training and by mid-1914 already had the logistics in place for her hospital; so much so that by September 1914 not long after Britain had declared war on Germany, Highclere Castle was ready to receive its first patients.

Others swung into action with the aristocracy and the rich opening up their homes as hospitals and convalescent homes. These included Woburn Abbey, Harewood House, Blenheim Palace, Glamis Castle, Wrest Park, Dunrobin Castle, Elmswood and Taplow Court. Other country homes such as Clandon Park and Attingham Park housed Belgian refugees who had fled the German advance while Halton House became a training depot complete with dug out trenches to simulate the conditions on the Western Front. In major cities such as London there was a need for more beds than any existing hospital could offer so aristocratic townhouses such as Londonderry and Grosvenor Houses also became military hospitals. Certain aristocratic women such as Millicent Duchess of Sutherland and Shelagh Duchess of Westminster went one step further and set up hospitals in France close to where the fighting was, and although their sense of duty and hard work were appreciated the army sometimes found these aristocratic nurses irritating. Millicent Duchess of Sutherland for instance was known as “Meddlesome Millie” for her various charitable endeavours and crusade for worker’s rights before the war. When the First World War broke out, she worked with the Red Cross and established an ambulance unit in France which by the end of 1914 had grown into a 100 bed hospital near Dunkirk.

While young aristocratic men enlisted in record numbers (by 1915 Vanity Fair calculated that there were 800 peers or sons of peers fighting in the army and navy), their sisters, wives, fiancées and other female relatives turned to nursing, although not without objections from their elders. Lady Diana Manners, a daughter of the Duke of Rutland was one who was determined to do her bit as she recalled in her autobiography The Rainbow Comes and Goes:

I began scheming to get to the Front as a nurse. Women were taking Red Cross hospitals and dressing-stations to France, and they were taking their daughters and their daughters’ friends. I wrote to the Duchess of Sutherland and the Duchess of Westminster and others……I got nothing but discouragement and tears from my mother and a pi-jaw from Lady Dudley, whom my mother summoned to reason with me. She explained in words suitable to my innocent ears that wounded soldiers, so long starved of women, inflamed with wine and battle, ravish and leave half-dead the young nurses who wish only to tend them. I thought her ridiculous and my mother ridiculous too, and could not believe Rosemary Leveson-Gower, my cousin Angie Manners and other girls I knew already in France to be victims of rape.

Regretfully I abandoned the Front in favour of nursing at Guy’s Hospital (Aunt Kitty’s refuge many years before). This took a stiff fight, but as an alternative to rape at the Front the civil hospital was relieving to my poor, poor mother.

The likes of Almina Countess of Carnarvon, Millicent Duchess of Sutherland, Mary Duchess of Bedford and Lady Diana Manners (later Cooper) were not simply “show nurses” but were actually trained and in time could assist in operations. Many of them had knowledge of the administrative side of hospital work by serving in committees and hospital boards before the war but practical knowledge was something they acquired during the war. Mary Duchess of Bedford was a classic example: having established a small cottage hospital not long after her husband succeeded to the dukedom, she wasn’t content with merely becoming a figurehead but also began to attend medical lectures at London Hospital: and they stood her in good stead when the cottage hospital was expanded and enlarged. She came into her own when during the outbreak of the war and Woburn Abbey was turned into a military hospital. Sister Mary as the Duchess became known not only made sure that the house was well equipped and could cope with the huge number of casualties but also that the patients and nurses had access to leisure and entertainment as well as fresh air and ventilation, which she believed would help with the soldiers’ recovery and provide a respite for the nurses having to deal with the wounded and the dying every day. She worked 16 hour days and by 1917 had qualified as a surgeon’s assistant and began training in radiotherapy.

For younger aristocratic women, their war work gave them a glimpse into a side of life and interaction with other people that they would not have otherwise encountered, and equally importantly, for the first time in their lives they had a sense of purpose and achievement as Lady Diana recalls:

I enjoyed the months at Guy’s. V.A.Ds (it was the first month of their infancy) and there were but two of us were very well received. We dressed the same as the staff and were treated in exactly the same way. I was allowed to do everything the upper nurses were allowed, except dispensing, but in a few weeks’ I was giving injections, intravenous and saline, preparing for operations, cutting abscesses and once even saying prayers in Sister’s absence…..The life was excessively hard if you were not strong.

In light of these examples, it’s baffling that the Crawleys had to wait until 1916 to get behind the war effort, until 1917 for the Abbey to be turned into a convalescent home and even then the family does so grudgingly and with poor grace – Robert’s reluctance for this to happen is especially puzzling given his keenness to fight. (You have to wonder how the man who can’t bear even to give up part of his library to wounded men would have dealt with life in the trenches…) It takes a middle class woman, Isobel Crawley to remind her aristocratic relatives of their duty. While Sybil turns to nursing with enthusiasm and Isobel works as an administrator, the other women sit back and do nothing (save for Edith who briefly works as a farm labourer then as the convalescent home helper). Cora is only pushed to do her bit because O’Brien stirs things up by intriguing against Isobel rather than any sense of duty, and what’s laughable, of course, is Cora expecting a pat on the back as if she’s the only peeress working in a hospital or doing her bit after waiting for three years to get off her backside. By this point her real life counterparts were already running hospitals, driving ambulances on the front line of battle, assisting in complicated surgeries and could give out injections and clean abscesses without batting an eyelash. That scene where Cora was expecting to be singled out for praise by a visiting general was so ludicrous and opposed to the likes of Almina Countess of Carnarvon or Lady Stirling Maxwell – who actually declined the honours given to them after the war with the view that they were serving the best they could as demanded by their station in life without any recourse to recognition.

Cora’s oldest daughter Mary is no better. While her younger sisters have thrown themselves wholeheartedly into war work, Mary is content to do nothing but mope. She lacks the imagination and initiative to do something and even Edith had to persuade her to sing to their patients. It begs the question of what’s she doing and what will Matthew think if he knows that she’s not doing anything and it’s not a very good omen for how she’s going to be if they do marry and she becomes countess.

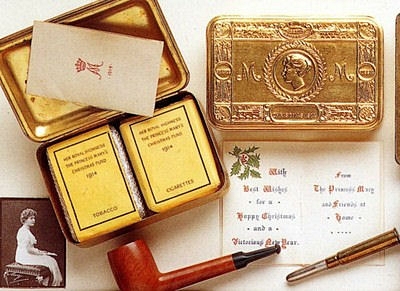

The abovementioned examples show how much Fellowes’ assertion that the Crawleys “haven’t really accepted the degree to which they can be helpful, because it will disturb their daily lives profoundly” and that “it’s realistic” are bunkum, as even the most cursory research would have shown. As the leading local family, the Crawleys would have been expected to set an example, step up to the plate and would have made preparations even before war was declared. Even if no-one else wanted to, Robert, with his sense of duty and eagerness to serve would be urging his family and the village to do their bit – as a Lord Lieutenant* he’d know war was coming because he’d know about mobilization in the county and through his old army comrades. They don’t need to wait for 2-3 years into the war and Sybil and Isobel to drag them kicking and screaming to do their part: for an aristocratic family, service and duty was something ingrained in them, but the Crawleys fail to demonstrate the public service that is expected of them and not doing anything would be commented on by friends and their wider society. Propaganda posters and newspaper articles during this period continually stressed the fact that the whole country was in it together – from the King down, high and low, rich and poor. The British royal family for a start from King George V, Queen Mary, their three older children and various relatives all did their part with the King even giving up alcohol, using the gardens at Buckingham Palace for the planting of vegetables and royal carriages and horses deployed to help transport soldiers to and from hospitals. Queen Mary was highly active in getting women involved through knitting and sewing comforts for soldiers in the front as well as establishing a fund for unemployed women workers which led to a working relationship with the trade unionist Mary Macarthur. Her only daughter Princess Mary worked as a nurse and started a fund which sent those now famous boxes filled with home comforts to soldiers and sailors serving in the Front. Even the old Queen Dowager Alexandra played her part with her hospital visits and expanding her Queen Alexandra Rose Day initiative to raise money for the soldiers.

The above mentioned examples demonstrate that everyone was expected and encouraged to contribute to the war effort. Royal encouragement was a very powerful incentive and there was a lot of public pressure for instance over women sending their men to enlist (more of which I will touch upon in part 2). This is very much a time when people ‘look up to their betters’ who were in their turn expected to set an example. Going to church every Sunday. Setting a moral example. Sending your sons to enlist in the army and your daughters to be nurses. Giving up your home for use as a hospital. This was part and parcel of the duty that the aristocracy were supposed to live by and those who didn’t do their duty were very much frowned and commented upon.

This inertia on the family’s part reminds me of something that occurred to me as Downton Abbey progressed through the series – that Fellowes actually despises the values and outlook of the traditional established aristocracy and is pointing out their uselessness and unwillingness to get involved as a sign that they serve no useful purpose: but then I realised that really he isn’t at all interested in portraying historical events to educate and enlighten and entertain. It’s simply a distortion of history (something to which he’s very prone) in the interests of plot. The plot, of course, is that Mary and Matthew become man and wife, in course of time earl and countess in the inevitable happy marriage, and that when they take over Downton can flourish in the hands of a progressive, modern owner, not the backward looking one it suffers from now. The upper middle class boy elevated to the ruling class (and God forbid I should suggest that for Fellowes the character of Matthew Crawley is in any way autobiographical) will show the peerage how to run their estates in the bold and modern world. Everything else, including global war, is a sideshow to serve that purpose.

Now I can already hear the cries of ‘But it’s fiction! A writer is entitled to do what s/he wants with historical events to create drama!’ and of course that’s true, thanks for proving my point for me. It IS only fiction, not a documentary. Leaving aside the fact that complete historical accuracy is not achievable anyway and no-one with any historical knowledge would claim that it is, Fellowes is only following in the giant footsteps of Shakespeare when he re-writes historical fact to entertain and a great deal of historical writing is essentially dependent on interpretation anyway. There is a whole debate about whether or not the writer of historical fiction has a duty to present the facts and what sort of distortion and re-writing is acceptable in the name of entertainment that I don’t propose to start here. My objection is that throughout the six series of Downton Abbey we have been assured that it is historically accurate down to the smallest detail, and that a historical adviser is on hand to make sure that no errors slip through.

This, I can tell you, is arrant nonsense. For many people boo-boo spotting the errors in Downton became an entertaining minor sport: and if Downton Abbey had ended after a couple of series the slips up, solecisms and errors would have been no more than an easily forgotten petty irritation. As it was the series became a world-wide hit with millions of fans who regard Fellowes as an expert on this period and take his very partial and distorted view of history as gospel because of that oft-repeated declaration of complete historical accuracy – and in series 2 he doesn’t just re-arrange historical fact to suit the drama, he actively suppresses fact by declaring things to be true that definitely aren’t and that even a brief reading on the war show to be wrong. Like Robert not fighting because he’s too old and because he’s a landowner. That is my gripe – that he says categorically this is true and happened like this when truth is no it didn’t, it happened completely differently which I will touch more upon in the next part.

*Although, of course, we don’t know until a later series that he IS a Lord Lieutenant. That’s another plot device that comes and goes like Bates’ limp. Incidentally, for those who are wondering, the Lord Lieutenant of a county was at the time a leading aristocrat who was the monarch’s direct representative in his locality. Had we known that it would make Robert’s reluctance to have his home turned into a hospital even more ludicrous: as the crown’s representative people of all classes would look to him to set an example right from the start of the war, and there’d be questions asked at very high levels if he didn’t.

Further Reading:

Gavin Roynon (ed) Home Fires Burning: The Great War Diaries of Georgina Lee (Stroud, 2006)

Jerry White. Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War (London, 2014)

Terry Charman. The First World War on the Home Front (London, 2014)

Kate Adie. Fighting on the Home Front (London, 2013)

Lucy Lethbridge. Servants (London, 2013)

Fiona (Herbert) Countess of Carnarvon. Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey: The Lost Legacy of Highclere Castle (London, 2011)

Julian Fellowes. Downton Abbey: The Complete Scripts Series 2 (London, 2013)

Jeremy Paxman. Great Britain’s Great War (London, 2014)

May Byron (with introduction by Eleri Pipien). The Great War Cookbook (Stroud, 2014)

Lillie Scales. A Home Front Diary, 1914-1918 (Stroud, 2014)

Brian and Brenda Williams. The Pitkin Guide to the Country House at War 1914-1918 (Stroud, 2014)

Jessica Fellowes. The World of Downton Abbey (London, 2011)

Simon Greaves. The Country House at War (London, 2014)

Jane Dismore. Duchesses: Living in 21st Century Britain (London, 2014)

Diana Cooper. The Rainbow Comes and Goes (London, 1958)

Ian Kershaw. To Hell and Back: Europe 1914-1949 (London, 2015)

David Cannadine. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London, 1990)

Andrew Marr. The Making of Modern Britain (London, 2009)

Anne de Courcy. Society’s Queen: The Life of Edith Marchioness of Londonderry (London, 1989)

A well-researched and very interesting article, with greater literary merit than any of Fellowes’ scripts! You obviously have countless issues with the TV series, and you are patently no fan of Julian Fellowes. I agree that to skip over the first years of the war, with due disregard for the battles you mention, as well as the fighting against the Turks, is unforgivable, though mainly for the trite reasons given in explanation.

They may claim to be 100% historically accurate, but any informed viewer over a certain age can easily realise that this is not the case. The problem comes when uninformed viewers start to see this drama as fact. And fact based on actual events, at that. I look forward to more from you about this.

(I should add that I watched all the episodes, and enjoyed some of the story-lines. I never once took it seriously, and regarded it as little more than a costumed soap-opera to while away a Sunday evening.)

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks. I do not mind if liberties are taken for the sake of the narrative but they must be anchored in truth. For instance in “Victoria”, there was an allusion to an affair between Princes Ernst of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and the Duchess of Sutherland which patently never happened but it demonstrated how morality was making that transition from the more libertine 18th century and Regency mores to the Victorian and middle class one.

And my main gripe with Downton Abbey is precisely what you’ve raised – uninformed viewers who begin to see this porgramme as gospel truth and that Fellowes knows what he’s talking about when patently he doesn’t.

I did enjoy a few of the story lines but for me they were not enough to overlook what I saw as a misrepresentation of the era this programme is set in.

LikeLike

Out of interest, did you ever watch the original ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’? I would love to hear your opinion of that series. (I was completely hooked!)

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLike

Bits sadly. It’s part of our plan to watch the programme and review it as well as the new Upstairs, Downstairs. But from feedback I have received from many people, they have said its very, very good; far superior to Downton Abbey.

LikeLike

The original series was one of my stand out dramas of the 70s. Of course, it was studio-bound in the main, but it still boasted some wonderful performances. That more recent remake was nowhere near as good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that’s one of the ironies of period drama – the studio bound ones from the 1970s and 1980s were much better in terms of acting and writing. Edward the Seventh was another one from that same period that was very good as well.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed that, and ‘The Duchess of Duke Street’ too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Annette Crosbie for me in the definite Queen Victoria. I did watch “Duchess of Duke Street” but that was fairly a long time ago and yes that was excellent as well

LikeLike

And it must be watched in sequence, as it is very much a ‘serial’, in the old accepted sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for the tip and I’ll keep that in mind.

LikeLike

An excellent article. I’m looking forward to Part 2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks and stay tuned!

LikeLike

Very well done article.

My exposure to Downton Abbey is limited to watching part of a single episode set sometime during World War One and not being impressed in any sense, so I’m not a good judge of the show. But even if you haven’t seen it, this article is very interesting in its own right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment and the irony is that for all its flaws, series 1 & 2 are the most decent in all the six series of Downton Abbey!

LikeLike